Personal data in Government is broken

This post is based on a talk I (Simon Worthington) have given at the Institute for Government, London Borough of Hackney and Citizen Beta about the Personal Data Exchange project. Much of the material in this post is the combined effort of the wonderful Personal Data Exchange team, and references the user research we carried out and documents we produced.

You don’t have to speak to many people to work out that something is very wrong with personal data in Government. There are stories from every side of citizen-facing services – from citizens themselves and from within services and Government departments – that the way in which citizens have to apply for services causes a large amount of friction and pain.

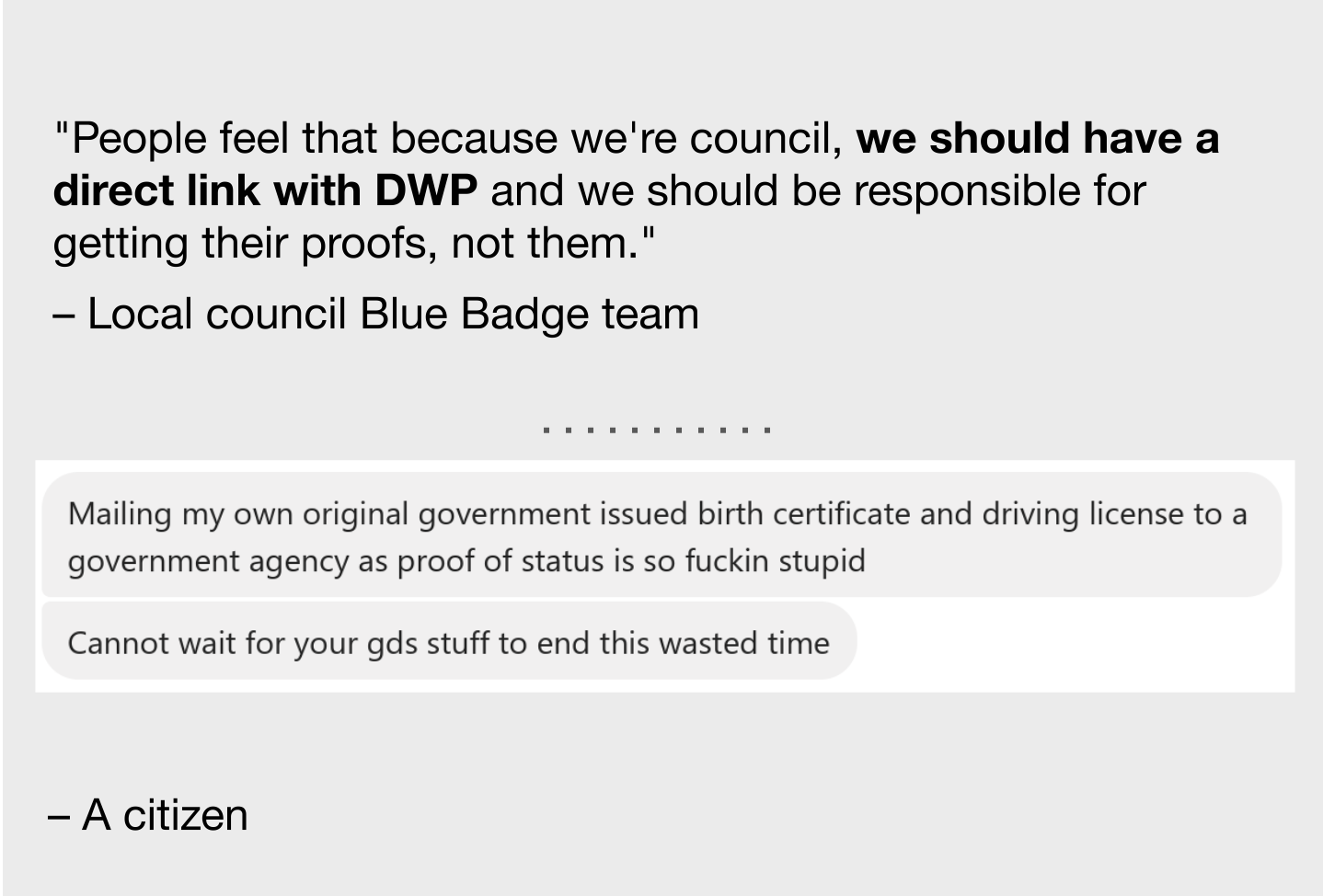

Citizens often have to provide proof with their application that they are eligible to receive a service. Often, the proof required is a piece of information held by another part of Government. For example, citizens submit evidence of their Personal Independence Payment (PIP) in order to show their eligibility for a Blue Badge parking permit.

Collecting, sending, processing and storing this evidence makes up a large amount of the work done by citizens and services, and citizens quite rightly don’t understand why they are forced to tell Government things it already knows.

People expect Government to operate like one organisation. But it does not.

Government is federated, and personal data is split between many databases in different departments. This is by design – by law, we deliberately avoid a “Big Brother” database containing everything Government knows about it’s citizens. This works perfectly well a lot of the time: departments collect the data they need to provide their own services, and keep it safe within their own walls.

Problems occur when a service relies on data held by a different department. There is no right for them to automatically access it, and no easy way to get hold of it. Services are forced to get that data via the citizen, who has to collect and submit data from all over Government to prove their need for the service.

Citizens find this confusing because the proofs they are asked to submit were not designed to be used as proofs. They are often letters sent by a department, containing many pages of other information.

In order to understand what to submit, citizens have to understand the eligibility criteria for the service, and these can often be complicated. See, for example, the eligibility criteria associated with a Blue Badge parking permit and observe how much a citizen needs to understand about benefits in order to work out what they should submit.

If they manage to work out what evidence they need, citizens still often get submission of it wrong – sometimes they submit a whole letter, or only the pages they think are relevant, or pages with some important information deliberately removed for privacy. This is if the citizen even has the letter at all – they may have lost it or destroyed it, and getting another takes a lot of time. Going backwards and forwards with citizens to get the correct evidence accounts for a large proportion of caseworker time and money spent in services.

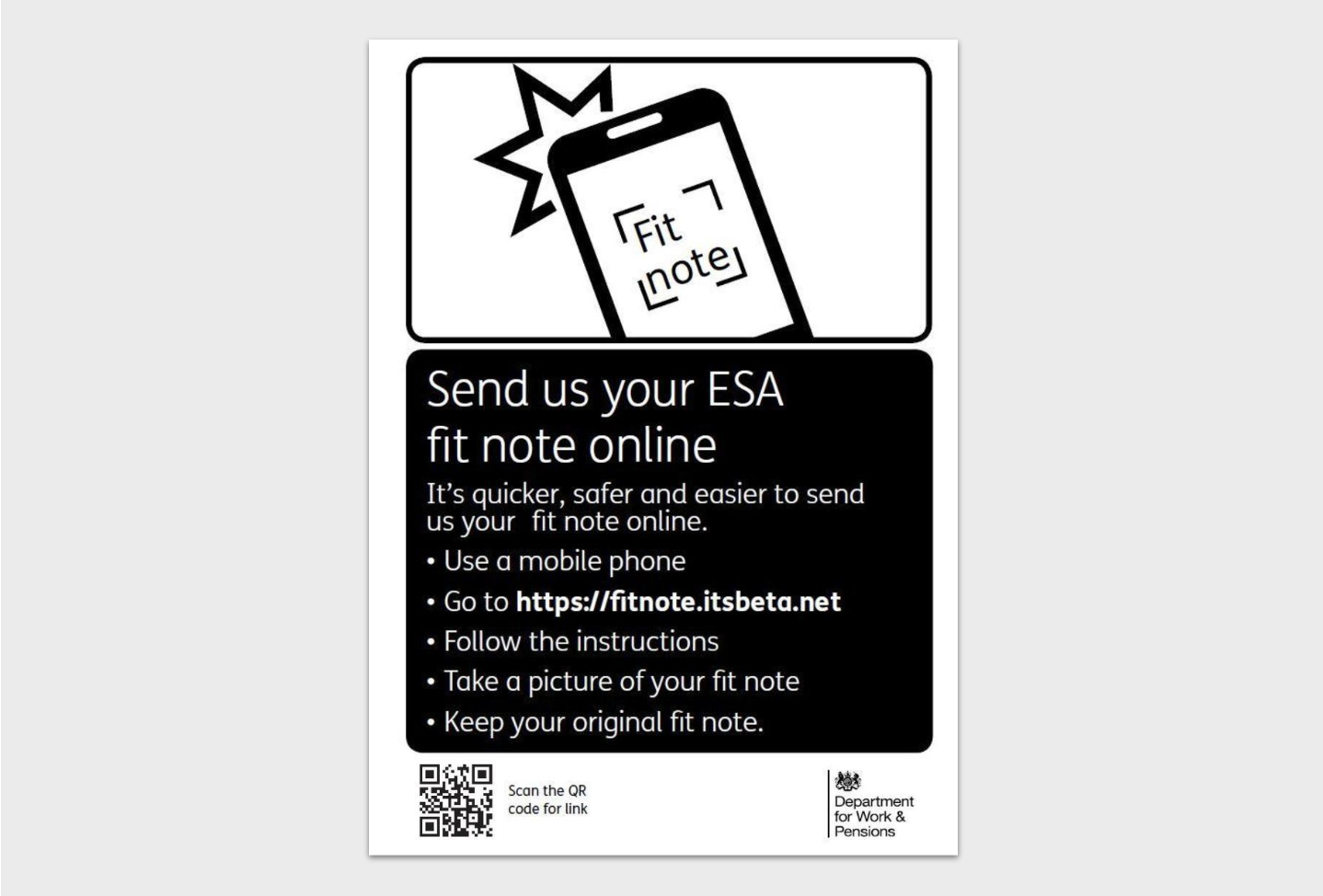

Citizens also struggle to actually submit evidence. Popping their sensitive personal information in the post isn’t partiuclarly comfortable. Services then have to do lots of manual processing with evidence and pay for it to be retained. Where electronic submission is available, many citizens lack the digital literacy (or equipment) required to submit something electronically. Services have to shoulder the burden of dealing with electronically submitted images that are too low quality to be used.

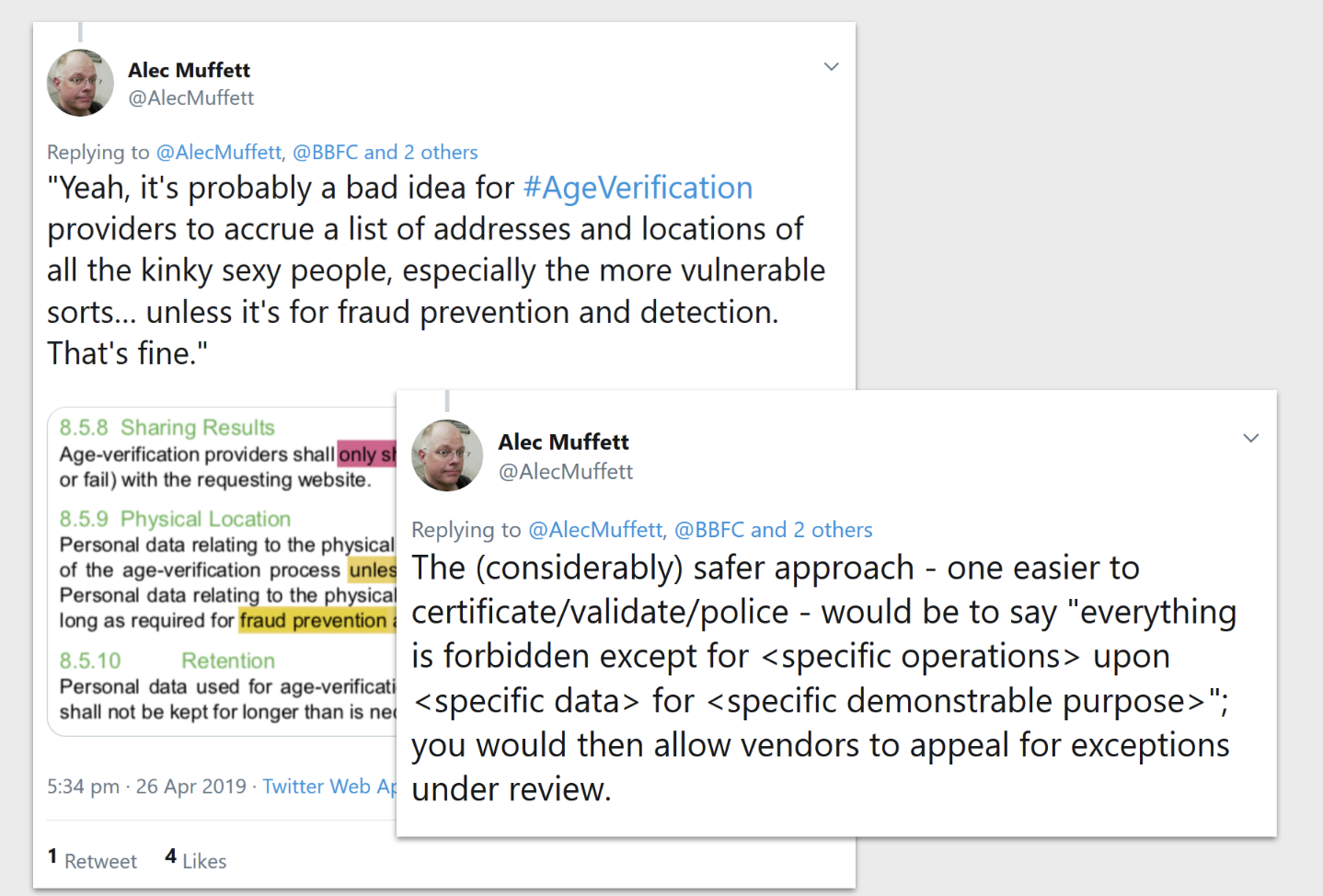

Even when evidence correctly makes it to a service, there are open questions about proportionality – letters often contain far more personal information than the service needs to know.

There is a clear incentive for services to make this pain go away. Increasingly, the solution they are turning to is to make submission of evidence easier, rather than getting it directly from the source. Why is this? Given that Government holds the data for use by Government, why do services struggle to get hold of it directly?

The short answer is that as soon as a department shares it’s sensitive personal data, it loses control over it. Deparments that hold data fear that other bodies will lose or misuse it. Their need to protect the citizens they have collected data about and worries of newspaper headlines and reputational risk are strong motivators.

Departments have little incentive to expose themselves to this risk. They minimise this risk to themselves by placing high legal, technical and security requirements on anyone who wants to get access to their data. They often also charge for the resources it takes to implement the sharing on their side.

Typically, setting up a data share takes anywhere from 12-24 months and many tens of thousands of pounds in legal discussion and technical development. This is not a bill that the majority of Government services (i.e. those with less than 100,000 transactions annually) have the time or resources to meet.

Even when services and data holders can work together to set-up a data share, reuse of the technical and legal elements between data shares of a similar nature is minimal. In one instance of data sharing between two large central Government departments, a new data sharing agreement based on the same data took the same two years of legal discussion, and incurred similar costs.

Clearly, there would be huge benefits (both financial and for the citizen experience) of solving this problem once for Government.

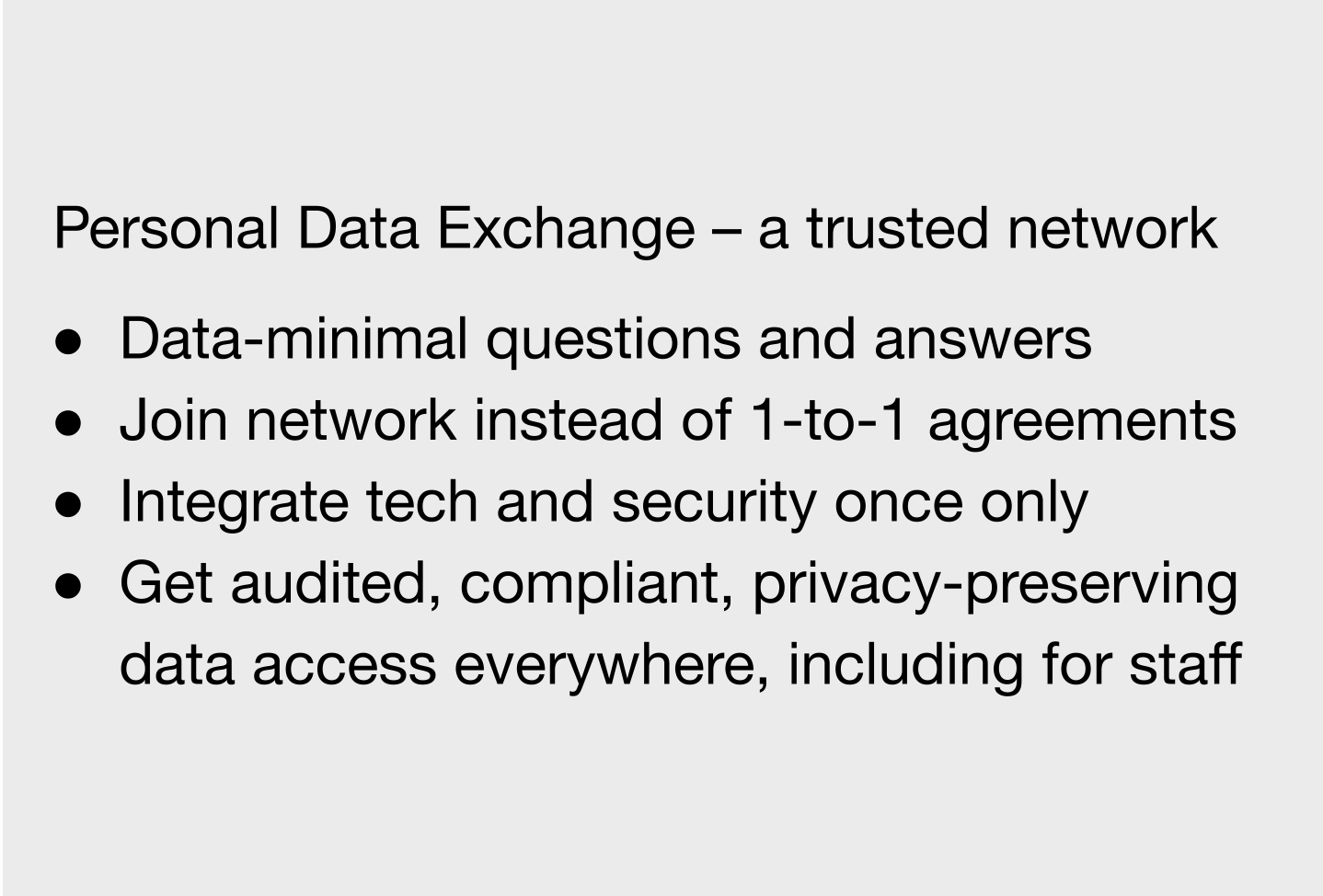

Such a solution would have to lower the risks faced by departments by minimising the value of what they shared. It would also have to make legal agreements and technology easier to implement for each service, and maximise the re-use of both of these, so that small services could justify doing this work once and re-using it over and over agian.

The solution would also have to face up to the “multi-channel” nature of citizen-facing services – it couldn’t just be digital. Many citizens still want to access services via phone, post or in-person, and this isn’t going to change. The solution, therefore, has to provide the same experience in all of these situations – a citizen applying over the phone shouldn’t have a degraded experience compared to one applying online.

With Personal Data Exchange, we realised that a cross-Government data infrastructure was the correct way to deal with both the high risks and lack of reuse. By having good sharing designed once for reuse, and including a standardised legal agreement and technical architecture, the cost to services and departments could be significantly reduced.

The model advocated by Personal Data Exchange was to provide a network of data sharers who had all been accredited to a minimum level and who had integrated a common technical platform. The common elements meant a lot less work each time a data share was implemented. The nature of these also meant it would be easy to re-use an existing share with another network member.

Each network member devolved assurance of who was in the network to a recognised authoritative body. In addition to setting the legal and cyber security requirements, the authoritative body would also be responsible for ensuring new proposed data sharing was proportionate.

We did user research with services, departments and citizens, built an MVP tech standard and demo, and developed a set of system design principles.

We must act now to solve this problem. People are already starting to do large scale personal data sharing, and on the whole they’re doing it badly.

It took many years of research for the Personal Data Exchange team to understand what cost-effective, successful, ethical, and privacy-preserving data sharing looks like, and we cannot expect everyone around Government to be able to invest this time.

Government must step up, show leadership on this problem, provide guidance on how to do personal data sharing well, and – ultimately – solve the difficult legal and technological problems once, for all of Government and for the good of citizens. Without doing this, we risk people making big and costly mistakes, and it’s the subjects of the personal data that will end up paying the price.